‘Art knows no boundaries’: Will Western audiences see this new Russian blockbuster?

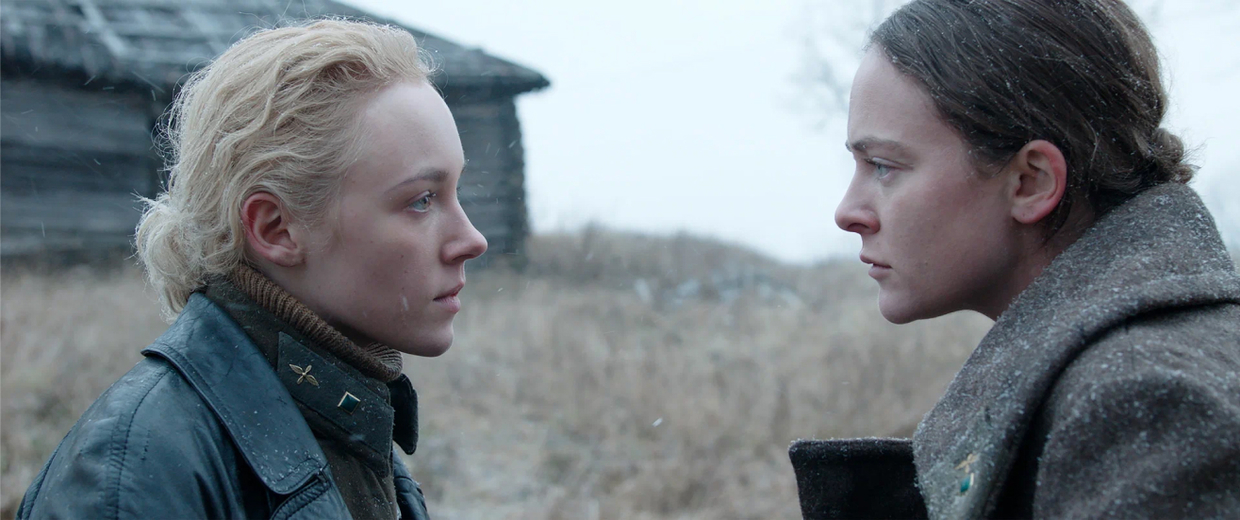

‘Vozdukh’ (‘Air’) – a new film by Alexei German Jr. (best known as the director of the movies ‘Garpastum’, ‘Paper Soldier’ and ‘Under Electric Clouds’) – was released to movie theaters across Russia in late January. It tells the story of female pilots on the Eastern Front of World War II. Despite sanctions and the exclusion of Russian movies from foreign film festivals, ‘Air’ premiered at the Tokyo International Film Festival and was also shown at the Festival of Young Cinema in Macau (China).

Here Elena Okopnaya – the film’s co-creator and production designer – tells RT about the world premiere of the film, the role of women in cinema, and the ‘cancellation’ of Russian culture in the West. Okopnaya is the recipient of a ‘Silver Bear’ award from the Berlin Film Festival.

RT: When people watch modern Russian war films, they don’t expect to see anything like ‘Air’ – especially considering the kind of movies produced in the past few years. It is really an iconic film. Do you think there is demand for such large-scale and complex war films, both in Russia and abroad?

Elena: In this regard, ‘Air’ is a great example, it shows us that there is hope. The box office success in Russia was huge and almost unbelievable, especially considering that this is an arthouse film. Frankly, before the release, we [the creators] were in extremely low spirits, we had this feeling that art is moving in an uncertain direction and no one needs serious, large-scale films anymore.

But it turned out that we had underestimated our audience. People need films that challenge them, they want to see real emotions on screen and experience a kind of inner breakthrough that leaves them feeling optimistic. They don’t just want another simple story based on two uncomplicated thoughts put together.

‘Air’ is a unique film because despite the use of state-of-the-art technologies and special effects, some of which were created specifically for this motion picture, it remains an arthouse film which means it’s a work of art. This is not a classic blockbuster, where special effects often overshadow the characters – in other words, the human presence. Because we really need that human presence [in cinema] – and by ‘we’, I don’t just mean the creators of the film but the audience as well.

I think this is a positive trend, which hopefully will develop further.

RT: A trend towards more complex cinema?

Elena: Yes. I’m primarily concerned with complex people – both on screen and in the audience. The problem is that we live in an era of clip thinking. But viewers need to see more than just flashes and explosions [on screen] – they also need to live through challenging situations.

I remember how Alexey German’s film ‘My Friend Ivan Lapshin’ was part of a special competition at the Venice Film Festival, where restored versions of classic films were shown. After watching some of the movies from different countries, it seemed to me like the same film was being shown over and over again – the plot, characters, and the artistic images in these movies were all identical. They were good, ‘solid’ films, but they no longer had a particular ‘face’ – the individual characteristics of the director or the country. Of course, throughout the years, the Venice Film Festival introduced many great films and filmmakers to the world. Perhaps that time, I just wasn’t lucky.

As a result, I felt kind of sad and went to visit various museums with a friend. Suddenly, in one of the museums, a Russian-speaking volunteer came up to us and said: ‘I didn’t want to go to the film festival, but ‘My Friend Ivan Lapshin’ is my favorite movie.’ Of course, I was pleased, and I got him tickets. After the screening, he came up to me and said the words that still ring in my ears: ‘I love the director, I love the movie, but the background characters really distract from the movie’.

This is a good example of how we often perceive reality in a flat and simplistic manner. This creates a vicious circle: on the one hand, the audience is not ‘ready’ for complex movies, and, on the other hand, because of this fact, the directors and producers do not want to take risks and create art films.

Now, it seems to me that a different rhetoric and manner of communication with the audience are emerging [in modern cinema]. For example, consider the movie ‘Oppenheimer’ by Christopher Nolan.

I believe this is the only way out of the modern cultural crisis, which reproduces meaninglessness.

RT: How would you characterize this crisis?

Elena: No offense to journalists, but it seems to me that cinema, just like modern art, takes the bread out of the journalists’ mouths. This substitution is devastating.

For example, when I was on the jury of international film festivals, I had to deal with situations where certain people said that this or that movie should win because it was the ‘right’ type of movie. Sorry, but why is that? The film obviously wasn’t as good as the others. But as it turned out, it touched on an ‘important’ social topic and that’s why it had to win. Though of course, there are other situations as well.

It makes me want to ask: how are we evaluating the film – from a journalistic point of view or a cinematic one? It seems to me that the filmmakers themselves and the people who evaluate their work are responsible for this substitution – it’s the vicious circle which I’ve talked about before. Of course, cinema should be socially relevant, but cinematic language and talent are highly important evaluation criteria.

RT: But the movie ‘Air’ also has a certain social agenda: women at war. Why did you want to make this a story about women and their role in the conflict?

Elena: It’s not what I do that matters to me, but how I do it. Many movies about war are being shot around the world. But how are they made? What is their message? Do they show simple human beings whose courage we can relate to?

When making the film, I was terrified to think of how those girls made several sorties a day and operated wooden airplanes covered with percale (durable plain-weave cotton fabric – RT). I asked myself – what was going on inside those women who knew that each flight might be their last but still got into the cockpit? Moreover, there were many non-combat losses – the pilots fell asleep, the aircraft’s engine blew up… Some girls didn’t die a hero’s death, but they did their work anyway.

We wanted the audience to feel that ‘Air’ is not just a movie about heroism, but about many other things – about the good and the bad within us, about what breaks us and what lifts us up, about how we change and why we make a certain choice in difficult circumstances.

Oddly enough, I associate this story with ballet: dancers overcome pain and suffering out of love for what they do.

RT: Do you feel that there is a certain disregard for women in the global film industry?

Elena: Sure, this problem exists. I remember how I missed the Nika Award ceremony (Russia’s main national film award, presented by the Russian Academy of Cinema Arts and Science – RT) because we were filming ‘Air’. Afterwards, I received a lot of messages – my friends congratulated me on receiving the award and told me about the ceremony. It turned out that a very famous Russian artist came on stage and said: ‘God grant that a woman does not win the award, because women simplify our profession.’ I will only add that I did get the award.

Few people consider the fact that on my team, there were lots of women who put a great physical and emotional effort into this film. Of course, we need to talk about this more.

But there is also another side to the issue. For example, when women win awards just because they are women.

I think we need to keep a sense of balance and avoid extremes. This applies to both Russia and the rest of the world. There is less and less common sense in our world, and this is sad.

RT: ‘Air’ is a movie about women, the USSR, the 1940s, WWII… Do foreign audiences understand these themes? What do they think about the film?

Elena: I insist that a work of art is understandable for all viewers and knows no boundaries. We were wonderfully received at the Tokyo International Film Festival, where the world premiere of ‘Air’ took place. There were several screenings and discussions with the audience, and each time we got a full house.

The audience asked many subtle and precise questions. At the end of any conversation, it is very important to come to certain thoughtful conclusions. For example, one viewer said that our film speaks in whispers, and that was very important for me. He felt this, despite the explosions and the special effects.

Of course, there were questions about women. For example, the Japanese people were surprised that so many Russian women were involved in the fighting during WWII. By the way, that is what really pulled us together and made us realize that women are actually capable of a lot of things.

In addition to Japan, we were able to show the film in China — in Macau. At the Macau Festival of Young Cinema, there were fewer people than in Tokyo, but the film was also very well received. The audience asked many questions, and only some of them were about politics and the international situation. It is important to hold complex dialogues with people, they appreciate it a lot.

This is why I believe that ‘Air’ isn’t just a movie for Russian audiences, but for the whole world, because the world needs a more complex artistic language.

RT: Today, we don’t see many Russian films at foreign film festivals. How did you manage to bring the movie abroad?

Elena: I think the answer is simple: no one can cancel Russian culture. Also, both Japanese and Chinese audiences loved the film and I think they wouldn’t have thought it fair if they had said: we will no longer allow talented Russian films to participate in the festival.

We should understand that the world is not shut for us. There are many people who still look for art, find it, and bring it to audiences. Such people have different evaluation criteria – they are concerned with the meaning of the film and their own cinematic criteria.

For example, in our movie, some scenes were shot at the Hermitage Museum. It is a well-known fact that during the Siege of Leningrad, the museum’s curators tried to preserve many works of art. [The museum workers] were mostly fragile women who persisted in their efforts to save art despite pain, fear, hunger, and loneliness.

When you see this story, you immediately feel a connection and empathize with those people. It has nothing to do with your nationality, or what country you were born and raised in. For example, after the filming, I kept dreaming of a young girl who was wrapping up sculptures in blankets with frozen fingers. It’s not just about someone saving sculptures, it’s about saving the human being within ourselves.

That answers the question why we were invited to foreign film festivals. [Art] is a treasure that belongs to the entire world.

RT: In which countries apart from Japan and China will the movie be shown? Will viewers in the US, UK, Canada, and the EU be able to see it?

Elena: That will surely happen in the future. I know there are many people in the West who are interested in this film. We are often asked to share the link, we receive feedback. No one knows what this will lead to eventually. But I am sure that anyone who wants to see the movie will be able to do so. Because things that many people have poured their heart into (and ‘Air’ is exactly that type of film) have a life of their own and become part of a greater whole that knows no boundaries.

RT: We know that Russian movies have been banned from Western film festivals and streaming platforms. Who loses out in this situation?

Elena: We still have to work a lot and improve [our film industry] in order to answer that question.

In terms of art, we still have a lot to learn. I don’t believe that many of our films and series are worthy of being presented at film festivals, even in Russia. Many movies that no one needs are being made…

Regarding the film ‘Air’ – yes, people need to see it, otherwise they may miss out on something important. But unfortunately, few films like that are being made today. Although they definitely do exist.

RT: But we can’t say that modern Russian cinema has been underestimated at European film festivals. For example, in 2018 you received the ‘Silver Bear’ at the Berlin Film Festival for outstanding artistic achievement.

Elena: Until recently, things were fine, of course… But we weren’t the first ones to get ‘canceled’. When the ‘Iron Curtain’ finally fell, world cinema discovered many new filmmakers– like Kira Muratova and Alexey German. It turned out that the Soviet Union had treasures that the world didn’t know about.

What conclusions can we draw from this? Primarily, that there is a time for everything. We just need to develop [artistically], do our work well, and one day, people will find out about it.

RT: But even in Soviet times, the situation wasn’t as bad as now…

Elena: Yes, and when the situation in the world started changing, I was really scared. This is the very air I breathe – it is really important for people in the cultural field to cooperate, talk, and work together. We must ‘pollinate’ each other.

This is true not just for culture, but for sports as well. It really pains me that people who have devoted their entire life to sport cannot participate in international events and competitions, which are an integral part of their life (and I’m not even talking about Paralympic athletes).

But we have to keep fighting, and find other ways out of the situation, because all this is temporary.

RT: Hopefully, despite all the prohibitions and sanctions, culture has no borders…

Elena: I want to share a story. In 2018, we presented the film ‘Dovlatov’ at the Telluride Film Festival in the US. This is a ‘backstage’ kind of film festival in the Colorado mountains. The films are watched in a close circle which consists of both movie stars (like Nicole Kidman and Paweł Pawlikowski) and film lovers from all over the world.

When I was presenting our film, a huge line of people assembled in front of the hall. They all came to see modern Russian cinema. After the movie, the viewers came to thank me, and I felt like a star. It is really important to receive such feedback.

Why did that happen? Because the movie was about universal values, the ones we all share. Sure, after the screening, people asked me about the Soviet regime and how it treated Dovlatov. And I told them: ‘The movie isn’t about that. There are always circumstances that will try to crush you. So, OK, in the USSR, there was censorship, and it was difficult for people to do what they wanted.’ And then I turned to the audience and asked them, ‘And today, can you be yourself when you have to pay a mortgage?’. The reaction was instant. They knew exactly what I meant.

This film is about remaining true to yourself and preserving your identity, regardless of the circumstances – for example, writing the things you want to write, and conveying your vision and feelings despite all challenges.

To pull yourself together and remain true to yourself – that’s what counts. And it’s an important message for all of us.

When you find the key and really start speaking the language of your audience, people understand you – even if you are from different countries and cultures.

Sure, they may not understand certain details. Russian art is about the soul. But actually, Americans sometimes know Russians better than Europeans do. Although we often ignore the fact that people all over the world have a much more complex image of Russia and the Russian people than we believe.

RT: Even despite the cinematic stereotypes?

Elena: Of course! I remember a private party at the same film festival. A well-known US cameraman approached me and described his feelings about Russia. ‘When I watch your Russian movies, I see that sometimes, things are a lot more complex.’ It turned out that I didn’t have to prove anything. The situation is not hopeless and there is understanding between us.

RT: Have you preserved ties with foreign film critics, directors, screenwriters?

Elena: Yes, but we communicate less often. They are also hostages of this situation, in a certain sense... Some have more courage and reach out, others don’t. We are all human.

As I said before, at first I was worried because it’s tough to work on a movie for five years and then not have the chance to present it to the whole world, as we had done before. But we just need to wait, it’s a matter of time.

Sure, no one will celebrate the return of Russian cinema, but at least they won’t say that Andrey Tarkovsky is a Polish filmmaker... Of course, that’s on the verge of surrealism. It’s like they want to drive you mad by trying to prove that black is white and vice-versa.

RT: Why do you think the world has abandoned the idea that sport, science, and culture are outside of politics and borders?

Elena: It feels like everyone has abandoned the rules of the game and there’s total confusion – even in those aspects where culture used to be an instrument of ‘soft power’. But things cannot remain like that for long, and the ties between people cannot be broken.

For example, many countries participated in joint science and space projects. Can we all exist without such cooperation? I think that common sense will prevail. Hopefully, the necessary changes won’t come at a great price.

RT: Do you think that cinema can influence society, culture, and change the future?

Elena: For better or for worse – but yes, I believe it can. Cinema is about the formation of consciousness, about giving thoughts and feelings a direction.

When you give a child a difficult task, but don’t say that it’s going to be challenging, the child doesn’t perceive the complexity in the same way as if they had known about it in advance.

Many [artists] have forgotten about this, and keep teaching people their ABCs. It’s time to take a big step forward and get over it. I often get asked ‘Who needs that?!’ But people do need it – both in Russia, and in the US ,and in Japan. A new generation is emerging which is interested in more complex ideas, this language is more understandable for them. But for some reason, we keep speaking a different language.

RT: How does art respond to evil?

Elena: To respond to evil means not to adapt to it, to try to remain yourself, against all odds.

Of course, it’s not like you’re obsessed with that idea. It’s simply an internal concept which you can’t ignore, even if you wanted to. It’s the way you live, the way you speak, the way you create art. You don’t want to resort to a commonplace language, you want to talk about what is important to you, and at the same time you can freely discuss opposite concepts.

RT: At the beginning of the movie ‘Air’, the main characters ask each other, what is more important – one’s Homeland, or human life? At the end, the main character answers that question… But how do you answer it for yourself?

Elena: It is indeed a tough question. But all of us ask it sooner or later.

We are part of the [Russian] soil, and we carry within ourselves a certain shared experience, the literature and cinema which we all know. For example, when I feel down, I read Fyodor Dostoyevsky (though some would say, why make it worse and torment your soul?!)

But at the same time, I’ve always wanted young people to see the world and have a broad worldview. This isn’t about ‘canceling’ the Russian person within, but about broadening one’s horizons– because to understand a certain system, one must step beyond it.